Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, has increasingly become a modern societal health concern, though it has been known under different names for hundreds of years.

A Brief History of PTSD

Historical records suggest that people recognized various trauma symptoms following battle, such as nightmares, difficulty sleeping, or a rapid pulse. After the American Civil War, medical professionals attempted to create a diagnosis, which they called “soldier’s heart,” regarding the cardiac symptoms observed during panic attacks.

Sigmund Freud’s early career focused on studying “hysteria” in women, which he and his colleagues were able to connect to traumatic experiences.

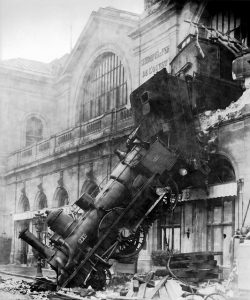

The Industrial Revolution brought “railway spine” in reference to people who experienced railway accidents and suffered ongoing psychological symptoms.

The Industrial Revolution brought “railway spine” in reference to people who experienced railway accidents and suffered ongoing psychological symptoms.

World War I called it “shell shock” or “war neurosis,” and World War II called it “battle fatigue” or “combat stress reaction.”

For decades, traumatic stress responses were seen as a weakness or failing, an inability to face the hardships of life; but after years and years of research and advocacy, we know this to be untrue.

In 1980, the diagnosis “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder” was developed in response to the numerous psychological symptoms seen by veterans returning from the Vietnam War. But these symptoms were noticed in civilians as well, who had never experienced military combat — for example, Holocaust survivors.

Lenore Terr documented the long-term psychological effects of the children who were involved in the 1976 Chowchilla Kidnapping, and the feminist movements of the 1970s continued to bring more light to the connection between trauma responses and sexual assault, rape, and domestic violence.

PTSD Today: The Statistics

Nearly 40 years after an official diagnosis was developed and validity was given to the experiences of trauma survivors, here are current statistics.

Overall lifetime prevalence in U.S. adults under the age of 75 is about 8.7%. That means, over the course of an entire lifetime, about 8.7% of American adults will meet criteria to be diagnosed with PTSD.

Yearly prevalence among U.S. adults is about 3.5%, meaning that over the course of twelve months, about 3.5% of American adults will meet criteria for a PTSD diagnosis.

There are higher rates of PTSD among women. Other risk factors include prior mental health diagnoses, childhood adversity, lack of support systems, lack of internal coping skills, severity of threat to personal wellbeing (or that of a loved one), dissociation during and extending afterwards, and for those who experienced combat, killing someone or perpetrating violence.

It is important to remember that just because a person experiences a traumatic event or traumatic amounts of stress does not mean they will fully develop PTSD. There are numerous mitigating factors — such as supportive people in a person’s life and well-attached parental relationships — that can help a person recover from trauma relatively efficiently.

Also, just because a person does not meet full criteria for a PTSD diagnosis does not mean they are not experiencing trauma-related symptomatology. These symptoms can happen along a spectrum, and trauma-informed therapeutic techniques can be used with people who may have experienced traumatic events, but do not meet full PTSD diagnostic criteria.

PTSD Symptoms

When evaluating a client for a diagnosis, PTSD symptoms often fall into one of four categories: re-experiencing, avoidance, arousal, and/or reactivity, and negative changes to cognition and/or mood.

The symptoms usually begin within three months of the traumatic event, and they need to be present for more than one month to qualify for a PTSD diagnosis. If it has been less than that, a diagnosis of Acute Stress Disorder may be considered. Please note that there are different diagnostic criteria for children.

Re-experiencing

This is a set of symptoms in which the survivor will “re-play” the event, either through flashbacks, nightmares, or vivid, intrusive memories. These can be triggered by external events (like seeing a similar face to one who abused you) or internal events (like a feeling that you felt moments before your trauma).

Avoidance

This happens either internally — blocking emotions or memories that remind you of the trauma — or externally — avoiding people, places, activities, objects, or situations that remind you of the trauma.

A straightforward example of this would be someone who avoids driving or being in a car after a motor vehicle accident, but it can also include things like drinking excessively in order to forget or filling time with binge watching shows in order to avoid silence and space to ponder memories.

An intense form of avoidance that can happen during the traumatic event and/or repeatedly afterwards is dissociation or depersonalization — when the trauma is so overwhelming that your mind sort of shuts down to protect itself. It can be felt in milder forms as physical numbness or as much as a person mentally removing themselves and feeling as though they are watching it happen from the outside.

An intense form of avoidance that can happen during the traumatic event and/or repeatedly afterwards is dissociation or depersonalization — when the trauma is so overwhelming that your mind sort of shuts down to protect itself. It can be felt in milder forms as physical numbness or as much as a person mentally removing themselves and feeling as though they are watching it happen from the outside.

Arousal and Reactivity

This can of course bring to mind the hyper-vigilant veteran who is always looking around corners for an enemy, but it can also include things like being easily startled, feeling unsafe everywhere you go, or feeling irritable or anxious.

Thrill-seeking or reckless behaviors can also be considered a symptom in this category. The arousal symptoms tend to be ongoing, rather than initiated by a trigger, and can interfere with sleep or concentration.

Negative Changes in Cognition and Mood

Trauma can affect the way our brain remembers and processes the world around us. This can lead to difficulty remembering certain aspects or timelines of the traumatic event. It can also be experienced in the form of negative thoughts or beliefs about self and the surrounding world.

For example, someone may come to believe “I am inherently bad” or “I am guilty” or “No one can ever be trusted.” It may also include a declining interest in enjoyable activities, and feelings of estrangement from loved ones.

PTSD Treatment Options

These general categories can encompass many potential symptoms. If you believe you or a loved on may be experiencing PTSD symptoms, talk to a provider about a diagnosis and next steps. But even if you do not have symptoms in every category, you can still benefit from trauma-informed therapy.

I wish there was one magic solution that would work to heal all trauma symptoms, but there simply isn’t. Different therapies will work for different people, depending on the person, presenting symptoms, co-occurring disorders (like substance abuse), type of trauma, and the mental health professional guiding the treatment.

Here are some trauma-informed therapies and interventions recommended by the VA:

Prolonged Exposure

This is a type of talk therapy in which the mental health professional and the client target distressing triggers/memories and avoidance symptoms. They work towards decreasing their effects by slowly increasing the amount of exposure to the trigger or memory.

Cognitive Processing Therapy

This is a mix of talk therapy and writing prompts that work towards processing the trauma and challenging and changing negative thoughts about yourself and the world. Sometimes writing can help distance distressing memories and give better perspective.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

This is a therapy in which the mental health professional will utilize bilateral stimulation while processing memories and cognitions surrounding the traumatic events. This requires the mental health professional to have completed extra trainings and certifications to utilize the protocols.

PTSD Coach (Free App)

This is a free app developed by the VA that can help someone both track symptoms and triggers, and use relaxation techniques (such as deep breathing, mindfulness, or guided imagery). It also helps you learn more about traumatic experiences and how they affect you.

I frequently recommend this to clients who struggle with anxiety, whether it is related to trauma or not, because the symptom management tasks can be very helpful when you feel panicked. And, it’s free.

Medication

Some medications have been shown to be helpful in managing PTSD symptoms. If you are interested in seeking out medication, you need to talk to a medical doctor or psychiatrist about what options might be right for you.

Other types of therapy that have been indicated as helpful methods of PTSD treatment can include:

Talk Therapy

There are several different types of talk therapy that mental health professionals may use to guide their treatment plans. These might include Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, narrative therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction, or Mindfulness-based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, to name a few.

Most will contain elements of learning how to manage and reduce physical symptoms, challenging and reframing distorted thoughts and beliefs, revisiting the traumatic experience in various ways until it is less distressing, and learning self-care and boundaries.

Somatic Therapies

Sometimes there are no more words left to describe your trauma. Different therapies have been developed that focus on bodily experiences and allowing the trauma to be released from where it is stored in the body.

Sometimes there are no more words left to describe your trauma. Different therapies have been developed that focus on bodily experiences and allowing the trauma to be released from where it is stored in the body.

This can include trauma-informed yoga, dance/movement therapy, play therapy for kids, and a more recently-developed therapy called Somatic Experiencing. These will all be focused around processing what aspects of the trauma are stuck in the body and learning how to let them go.

Next Steps for Treating PTSD Symptoms

If you feel like you may be experiencing some trauma-related or PTSD symptoms, please do not hesitate to reach out to a mental health professional or another provider to talk about how to get counseling or resources.

In the meantime, you want to make sure you are taking care of yourself. Eat a healthy, balanced diet and avoid substances that alter your mind. Try incorporating more exercise and reach out to loved ones to let them know you are struggling.

Here are some other helpful relaxation tools:

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

You can find guides for Progressive Muscle Relaxation on YouTube, or even the PTSD coach app I recommended earlier. This is basically focusing on muscle groups individually and tensing them before relaxing them again.

You progressively move through each muscle group (i.e. your forearms or your cheeks), tensing and relaxing until you have focused on each of your body’s muscles. Pay attention to the physical sensation of the relaxation.

Deep Breathing

This isn’t just taking in successive deep breaths — there is actually a technique to use for relaxation breathing. You want to make sure you are pulling air down into your diaphragm — as in, your stomach should move more than your shoulders when you inhale.

You also want to make sure you exhale as much as or more than you inhale. This can be observed through counting. Start with inhaling for a count of four, then exhaling for a count of five, and proceed from there.

5, 4, 3, 2, 1

This is a mindful exercise meant to bring your attention to your present physical senses and orient your mind to the present. Look for 5 things you see that you haven’t noticed before. Then listen for 4 things you can hear, 3 things you can touch or feel, 2 things you can smell, and 1 thing you can taste.

This is a mindful exercise meant to bring your attention to your present physical senses and orient your mind to the present. Look for 5 things you see that you haven’t noticed before. Then listen for 4 things you can hear, 3 things you can touch or feel, 2 things you can smell, and 1 thing you can taste.

Grounding

When your mind races to the past or future — the “What if’s” or “What could’ve/should’ve been’s” — you need to work on focusing your mind in the present moment.

Draw your attention to the now by focusing in on what your feet feel like. What does the ground feel like beneath you? Notice where your body is in contact with clothes or a chair, and focus in on those physical sensations.

You’ll find other relaxation tools in the PTSD Coach app, and there may even be other helpful apps you can utilize. But reach out for help, and take hope that what you are experiencing now doesn’t have to be the rest of your future. Healing from PTSD symptoms and traumatic experiences is possible.

References:

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Friedman, M. (2018). History of PTSD in Veterans: Civil War to DSM-5. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/what/history_ptsd.asp

National Institute of Mental Health (2016). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

Ringel, S. & Brandell, J. (2012). Trauma: Contemporary directions in theory, practice, and research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. Retrieved from https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-binaries/40688_1.pdf

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (2019). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/index.asp

Photos:

“Train Wreck,” courtesy of WikiImages, pixabay.com, CC0 License; “Emotional,” courtesy of MasimbaTinasheMadondo, pixabay.com, CC0 License; “Germany,” courtesy of Simon Migaj, unsplash.com, CC0 License; “Mindfulness,” courtesy of Lesly Juarez, unsplash.com, CC0 License